he Dog Days of Summer

It is 103°F at The Compound on Friday 11 August 2023 as I write this and, according to the Farmers’ Almanac, the last of the “Dog Days of Summer.” Would that it was indeed the last of the “the hottest and most unbearable days of the season,” when the heat is said to drive dogs mad;[1] but the forecast calls for more of the same over the next several days. Meanwhile, the news is reporting on the tragic fires on Maui, especially at Lahaina. The Hawai’i devastation joins a litany of results from incessant heat waves in recent weeks and other global warming induced threats. Among them was the ominous reappearance of malaria in the United States.[2]

A Google Search quickly reveals that the “Dog Days of Summer” are so-named because of their association with the “Dog Star,” properly called by astronomers α Canis Majoris[3]—the most prominent star in the constellation Canis Major, the “greater dog” that follows the hunter constellation Orion (hence the star’s popular name). Notably, it is the brightest star in Earth’s night sky making it somewhat portentous in the minds of ancient observers.

Ancient Egyptians knew the star as Spdt,[4] transliterated Sothis (Σωθις) by the Greeks. Egyptians had long noticed that the helical rising of Sothis marked the beginning of the annual inundation by the Nile River and the traditional beginning of the year. But, while the Egyptians had a good 365-day calendar, it lacked a leap-year type adjustment to compensate for the fact that an actual Earth year is about a quarter day longer. Thus, the calendar new year would move a day earlier every four years. Since the vital inundation happened about the time Sothis “rose” above the horizon just at dawn, it remained the logical way to mark a new natural year, called the “Sothic year.”[5]

The ancient Greeks referred to α Canis Majoris as Sirius, its name (Σείριος, “scorcher”) obviously referring to the period of uncomfortable heat heralded by its rising. They also seem to have introduced the phrase “dog days” (κυνάδες ἡμέραι). More interesting to me—because of my recent research interests—is the association of Sirius with a serious threat that accompanied the heat.

Malaria and Heat in Antiquity

As early as Homer (conventionally dated around 800 BC, but likely with older elements) we see this association. In the Iliad Homer describes Achilles’ approach to Troy as

. . . like to the star that cometh forth at harvest-time, and brightly do his rays shine amid the host of stars in the darkness of night, the star that men call by name the Dog of Orion. Brightest of all is he, yet withal is he a sign of evil, and bringeth much fever upon wretched mortals (Homer, Iliad 22.25-30).[6]

“Fever” here is the Greek word πυρετός, used by numerous classical writers to describe the recurring febrile symptoms that are clear indications of malaria. Malaria is a “vector-borne” disease caused by parasitic infection of the victim’s blood by protozoans of the genus Plasmodium transmitted during blood meals by female mosquitos of the genus Anopheles (the “vector”).[7] Because ancients did not know the cause of the disease, it was simply referred to as “the fever.” The notion that “noxious fumes” (miasma) caused disease led to the eventual name mal’aria; Italian for “bad air.” Different species of Plasmodium caused intermittent fevers of correspondingly varying frequencies, so writers in antiquity named them accordingly.

For example, 5th and 4th century BC texts attributed to the famous Greek physician Hippocrates describe the tertian, quartan, and “semitertian” fevers (Hippocrates, Epidemics 1, 3) identified with Plasmodium vivax, P. malariae, and P. falciparum malaria, respectively. The later Roman physician Celsus, writing in the first century CE, gave a more exact account of two types of tertian fever (Celsus, De Medicina 3. 3. 1-2): what came to be called “benign tertian” (P. vivax), and the “far more insidious,” eventually termed “malignant semitertian” (P. falciparum).

That more deadly species of malaria, P. falciparum, requires more consistently hot weather to reproduce in the gut of female Anopheles mosquitos. North of the Mediterranean, mid July and early August were just the ticket for P. falciparum! Thus, Homer’s correlation of the Dog Star and fevers . . .

Homer was not alone in making such observations. The late 4th-early 3rd century BC philosopher Theophrastus noted:

in the actual dog days, although the air is torrid, yet south winds blow, clouds form and trees themselves become noticeably fluid . . . this also occurs in man, and this is why the bowels are loosest at this time and there is a great incidence of fevers (Theophrastus, De Causis Plantarum 1.13.5-6).

The first century BC poet Tibullus connects the heat of the Dog Days to danger near water: “stay by the stream that flows from Etruscan source, stream not to be approached in the Dog-star’s heat” (Tibullus 3.5.1-4). Vitruvius, the 1st century BCE civil engineer and architect also noted that “through the winter, even the regions that are most pestilential, are rendered salubrious” (Vitruvius, On Architecture 1.4.4). He also warned, “places, however, which have stagnant marshes, and lack flowing outlets, . . . like the Pomptine [Pontine] marshes, by standing become foul and send forth heavy and pestilent moisture” (1.4.12).

The contemporary writer on agriculture, Columella, also warned against standing water in siting a farm and made a direct connection to mosquitos; “neither should there be any marsh-land near the buildings . . . for the former throws of a baneful stench in hot weather and breeds insects armed with annoying stings . . . from which are often contracted mysterious diseases whose causes are even beyond the understanding of physicians” (Columella, On Agriculture 1.5.3-6). The later writer on agriculture, Palladius, gave similar counsel:

A fen is by all means to be avoided, especially that which is from the south, or from the west, and which has been used to be dried up, because of pestilential diseases, and of the unfriendly animals which it produces (Palladius, On Agriculture 1.7.4).[8]

This observation on the drying of wet areas is important.

The Dog Days not only provide the requisite heat for P. falciparum to reproduce, they also dry wet areas allowing mosquito larvae to develop without predators (fish and crustaceans) in the remaining small puddles. Early Christian funerary inscriptions around Rome reveal a pronounced seasonal mortality rate, remarkably consistent with the double-whammy the Dog Days allow for P. falciparum.

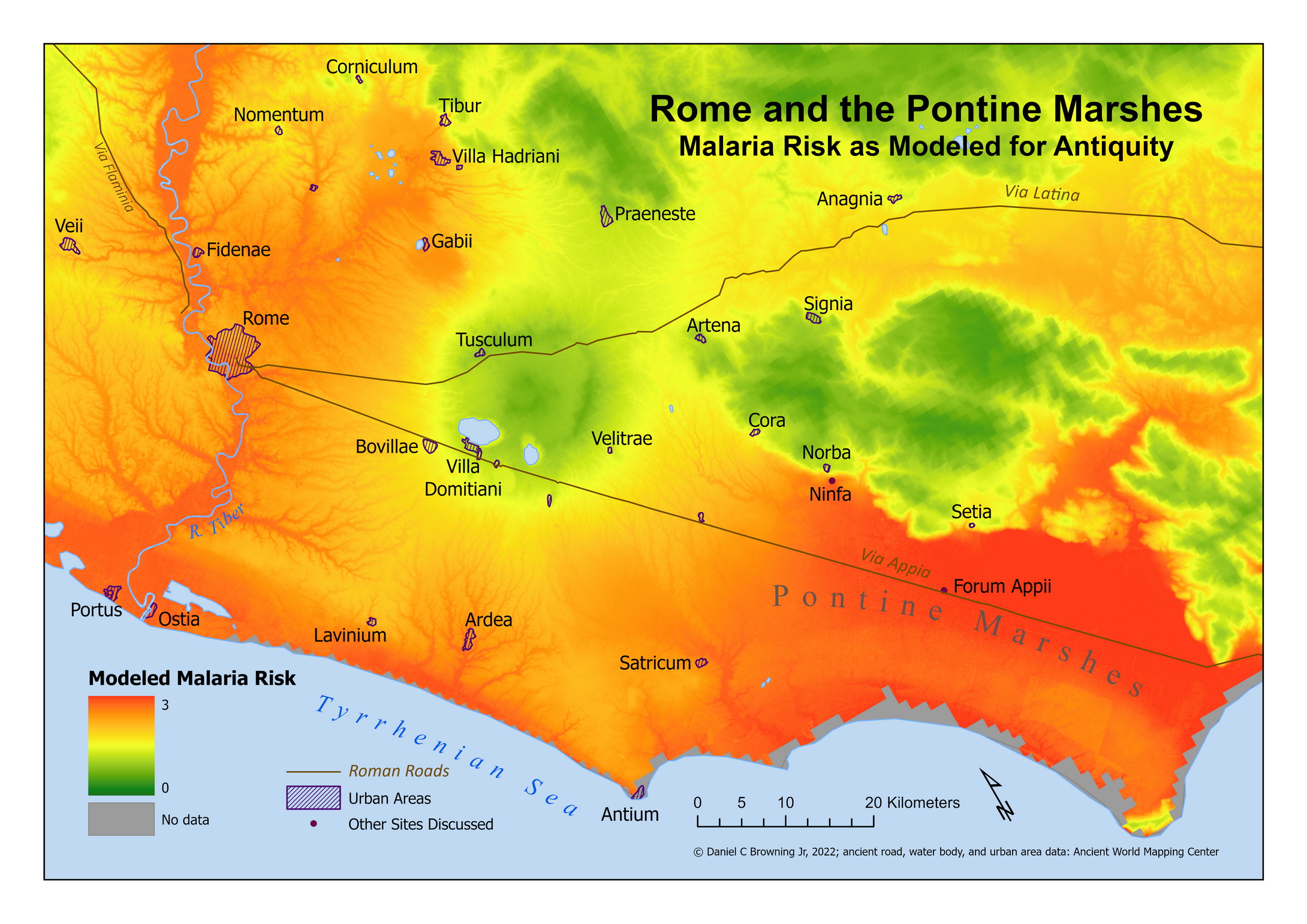

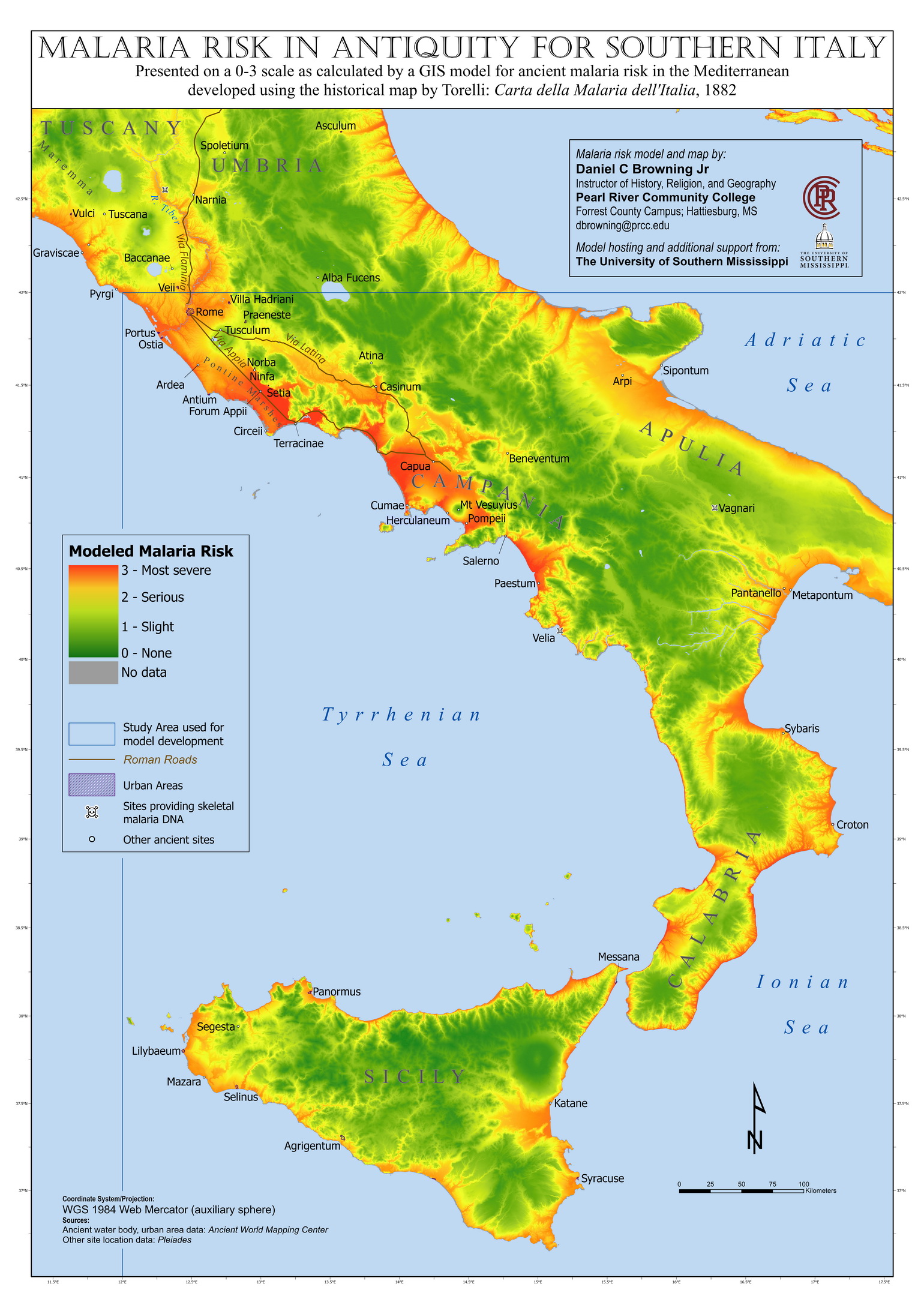

My interest in all of this stems from the notion that malaria, with its known health burden for ancient times, may also be a contributor to certain historical events or to their outcomes. To that end, I have created a spatial risk model for malaria in antiquity in the Mediterranean region; in other words, a study that outputs a map showing relative malaria potential for the region in ancient times. The final (so far) version of that model and its output was just published a week ago—fittingly, during the especially lethal Dog Days of 2023. It is a peer-reviewed and open access article. For those with sufficient interest, the article (with link) is:

- Browning Jr, Daniel C. “A Malaria Risk Model for the Mediterranean in Antiquity Based on the Historical Carta Della Malaria Dell’Italia.” Journal of Maps 19, no. 1 (2023): 2242724. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2023.2242724.

Beware the Dog Days of Global Warming

One thing that was hammered into my psyche from my three years of working on the malaria model for antiquity is this: small changes can make a huge difference in outcomes. The impetus for this blog post was the seemingly unending succession of huge outcomes this spring and summer that are due to the small changes wrought on our environment. I was not in the least surprised by the reappearance of malaria in the USA—BTW, the good news (for now) is that the reported cases are all P. vivax, significanly less lethal than P. falciparum, but still a threat to general health that cannot be ignored. Like most people, however, I was considerably moved by the suddenness of the catastrophe in Maui. It and the many other unexpected weather events of this year serve as early warnings of what could come.

To end on a hopeful note: small changes can make a huge difference in outcomes in a positive way as well. I hope we all can find our path to manage the labyrinth of an uncertain future.

Thanks for looking! ![]() (read the footnotes)

(read the footnotes)

[1] The “official” Dog Days are given by the Farmers’ Almanac as 3 July to 11 August and called “the hottest and most unbearable days of the season;” “What Are the Dog Days of Summer?” Farmers’ Almanac, https://www.farmersalmanac.com/why-are-they-called-dog-days-of-summer-21705. Accessed 11 August 2023.

[2] Emily Anthes, “U.S. Sees First Cases of Local Malaria Transmission in Two Decades,” The New York Times, 27 June 2023 (updated 3 July 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/27/health/us-malaria-mosquitoes.html.

[3] Wikipedia has an excellent entry on Sirius: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sirius.

[4] R. O. Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian (Oxford: University Press, 1962), 224. Ancient Egyptian script did not have vowels, so exact pronunciation is uncertain.

[5] Adolf Erman, Life in Ancient Egypt (London: Macmillan, 1894), 351, n. 1. The period it takes the Egyptian or Julian year to “rotate” so that the Egyptian or Julian calendar new year again falls on the helical rising of Sothis (1461 and 1460 years, respectively) is thus called the “Sothic cycle.”

[6] Unless noted, all translations of classical works come from the Loeb editions.

[7] For more detail, see either: Daniel C Browning Jr, “Malaria Risk on Ancient Roman Roads: A Study and Application to Assessing Travel Decisions in Asia Minor by the Apostle Paul” (Masters Thesis, Hattiesburg, MS, The University of Southern Mississippi, 2020), https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/728; or Daniel C. Browning Jr, “All Roads Lead to Risk: Malaria Threat to Ancient Roman Travelers.” Cartographica 56.1 (Spring 2021): 64-90. DOI: 10.3138/cart-2020-0028, and extensive references there.

[8] This translation is from: Palladius Rutilius Taurus Æmilianus, The Fourteen Books on Agriculture, trans. T. Owen (London: J. White, 1807).